Museums can be scarry places. To make the museum more inviting, the Northwest museums of Arts and Culture (or the MAC) installed the sculpture series, The Return of the Four-Leggeds. These sculptures are an exhibition, permanently on display outside of the museum and in the amphitheater.

Before entering the museum take a few moments to think about these statues. How many individual sculptures can you find for this work of art? What do the sculptures seem to be doing? Why do you think these sculptures are so active?

The Return of the Four-Leggeds is a collection of bronze sculptures was created by New York artist, Tom Otterness and was installed in 2003. Tom Otterness interpreted this work as:

“The Animal people have come with a contract to buy back the world from the Two-Leggeds. The Weasel is negotiating while the Salmon prepare the way to return to the river. The Marmot is already in the amphitheater, munching on small change.”

These statues present a fun an inviting look into social commentary as well as simply being pleasing to the eye. Take a moment, relax and reflect on The Return of the Four-Leggeds.

Monday, November 26, 2012

The MAC Revised

The Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, otherwise known as the MAC has changed a lot over the years. The organization began as the Eastern Washington Historical Society in 1916. The most notable donation to this society was the Campbell House in 1924, which is open and available for tours. In the 1960s the Cheney-Cowles museum was opened to exhibit the growing collections the historical society had collected. The Cowles family, who owns the Cowles Publishing Company, which owns the Spokesman-Review newspaper in Spokane, sponsored the Cheney-Cowles Museum. The Spokesman-Review was bought by the W.H. Cowles in 1893 and is currently in the 4th generation of Cowles family ownership. In 2001 the Eastern Washington Historical Society opened a new exhibition hall and changed the name to the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture.

Today the MAC is open Wednesday through Saturday to the public as well as tours of the Campbell House. The MAC has three main exhibition halls the museum. Admission to the MAC is $7 for adults, however admission is free during the 'First Friday' events, hosted on the first Friday of the month from 5-8PM, and BeGin events on the second Friday of every month from 6-8PM.

The MAC also operates The Joel E. Ferris Research Library and Archives to house all of its collections. These archives are accessible Wednesday through Friday 12-5PM, advanced notice is requested.

Today the MAC is open Wednesday through Saturday to the public as well as tours of the Campbell House. The MAC has three main exhibition halls the museum. Admission to the MAC is $7 for adults, however admission is free during the 'First Friday' events, hosted on the first Friday of the month from 5-8PM, and BeGin events on the second Friday of every month from 6-8PM.

The MAC also operates The Joel E. Ferris Research Library and Archives to house all of its collections. These archives are accessible Wednesday through Friday 12-5PM, advanced notice is requested.

The Campbell House Revised Again

Amasa B. Campbell was sent by wealthy Ohio speculators to investigate mining opportunities in the west in 1878. In 1892 Mr. Campbell made the front page of the Lawrence Daily Journal when he was caught in the midst of a mining dispute between unioned and non-union miners. Mr. Campbell and his business partner John Finch were ultimately very successful in founding the Standard and Mammoth mines in the vicinity of Wallace, Idaho. These mines became so successful that by 1903, they sold the mines for $3,000,000 to a joint venture backed by the Rockefeller and the Gould families.

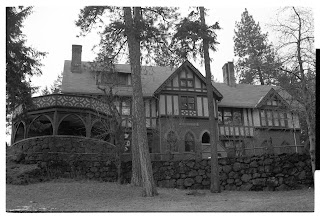

The Campbell House was built in 1898 and constructed for $30,000, although estimates for the house and the custom furnishings place the home at a total cost of $70,000. The Campbell House was home for Mr. Amasa B. Campbell, his wife Grace and their daughter, Helen. Renowned architect Kirtland K Cutter designed not only the architecture but the furnishings as well. One of the interior highlights of the home is the renowned gold reception room, which Cutter borrowed from the rococo French style. Life in the Campbell home was rigid, with social cues and interactions being paramount. To be invited to dinner at the Campbells was no small feat, the elite would dine formally, their meals prepared and served by servants, the men and women dressed in evening gowns and black ties accordingly. No house of this stature would be complete without a game room. The game room simply belonged to the men, who used the room to play cards and billiards, the game room was the 19th century equivalent of a modern man cave.

The house been restored from 1984-2001 by the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, who aimed to restore it as best they could. Unfortunately the original furniture was sold and the MAC has done its best to use photographs and accounts of the home to re-create the furnishings. In 1924 W.W. Powell (formerly Helen Campbell) donated the house to the Eastern Washington Historical Society, who is now known as the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. Guided tours of the house are available and are included in your entrance fee to the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, inquire at the admissions desk.

The Campbell House was built in 1898 and constructed for $30,000, although estimates for the house and the custom furnishings place the home at a total cost of $70,000. The Campbell House was home for Mr. Amasa B. Campbell, his wife Grace and their daughter, Helen. Renowned architect Kirtland K Cutter designed not only the architecture but the furnishings as well. One of the interior highlights of the home is the renowned gold reception room, which Cutter borrowed from the rococo French style. Life in the Campbell home was rigid, with social cues and interactions being paramount. To be invited to dinner at the Campbells was no small feat, the elite would dine formally, their meals prepared and served by servants, the men and women dressed in evening gowns and black ties accordingly. No house of this stature would be complete without a game room. The game room simply belonged to the men, who used the room to play cards and billiards, the game room was the 19th century equivalent of a modern man cave.

The house been restored from 1984-2001 by the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, who aimed to restore it as best they could. Unfortunately the original furniture was sold and the MAC has done its best to use photographs and accounts of the home to re-create the furnishings. In 1924 W.W. Powell (formerly Helen Campbell) donated the house to the Eastern Washington Historical Society, who is now known as the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. Guided tours of the house are available and are included in your entrance fee to the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, inquire at the admissions desk.

Patrick 'Patsy' Clark Mansion Revised

Patrick “Patsy” Clark was an Irish immigrant who came to the United States in 1850. Clark quickly left New York for the promise of mining opportunities in California. Clark was wildly successful in his mining overseeing operations and worked in mines from California to Montana and seemingly everywhere in between before working at the Poorman and War Eagle mines in Idaho. Patsy Clark became a well respected mine overseer and was even called upon for his expert opinion when mines were being sold that he was familiar with. In 1889 Patsy proved his business sense by selling the War Eagle mine to a group of investors for nearly 3 quarters of a million dollars in cash. When the new investors inspected their new mine, they found the ore was almost entirely exhausted and would have to begin searching for new reserves within the mine.

Patsy spent much of his life going from mine to mine, however finally settled down in Spokane in 1889 when he commissioned renowned architect Kirtland Cutter to build him a home. Patsy told Cutter to spare no expense in the construction of his home. Cutter finished the home in 1898, 9 years after Patsy Clark commissioned the home. The Clark Mansion stands as one of the most extravagant homes in the entire Northwest.

Kirtland Cutter spent years trying to create his vision. Inside of the extravagant mansion each major room, such as the Foyer, Drawing Room and Dining Room, had a different architectural style. In total the mansion has 27 rooms excluding the attic and basement. Furnishings inside of the mansion were custom built by artisans to Cutter’s specifications. The effect of the mixture of this one of a kind architecture and furnishings produced one of the most stunning homes in what became known as the age of Extravagance in Spokane.

The Patrick Clark Mansion has been used as a variety of things since Patrick and his wife Mary Clark died in 1916 and 1926 respectively. For roughly the first 50 years after the Clarks passed on the Mansion was used as a residence for various owners. The Mansion was then converted into the Francis Lester Inn, then into Patsy Clarks’ Resteraunt. Today the 2nd and 3rd floors of the Patrick Clark Mansion is used by NAME Architects, while the ground floor can be rented out for special events such as weddings.

Patsy spent much of his life going from mine to mine, however finally settled down in Spokane in 1889 when he commissioned renowned architect Kirtland Cutter to build him a home. Patsy told Cutter to spare no expense in the construction of his home. Cutter finished the home in 1898, 9 years after Patsy Clark commissioned the home. The Clark Mansion stands as one of the most extravagant homes in the entire Northwest.

Kirtland Cutter spent years trying to create his vision. Inside of the extravagant mansion each major room, such as the Foyer, Drawing Room and Dining Room, had a different architectural style. In total the mansion has 27 rooms excluding the attic and basement. Furnishings inside of the mansion were custom built by artisans to Cutter’s specifications. The effect of the mixture of this one of a kind architecture and furnishings produced one of the most stunning homes in what became known as the age of Extravagance in Spokane.

The Patrick Clark Mansion has been used as a variety of things since Patrick and his wife Mary Clark died in 1916 and 1926 respectively. For roughly the first 50 years after the Clarks passed on the Mansion was used as a residence for various owners. The Mansion was then converted into the Francis Lester Inn, then into Patsy Clarks’ Resteraunt. Today the 2nd and 3rd floors of the Patrick Clark Mansion is used by NAME Architects, while the ground floor can be rented out for special events such as weddings.

Friday, November 23, 2012

Digital Preservation

Digital Preservation is an intersting idea. There are great advanatages to digital formats, the largest being access. Wikipedia's article on Digital Preservation talks about the diferent strategies and types of digital preservation. The most important ideas, I believe, are those regarding Migration of data. For instance let's say I wanted to play the original Duke Nukem, which ran in MS-DOS. This game is on 3 1/2" Floppy Drives which are not even read by my computer. Digital preservation can come to the rescue. The migration of this data would mean finding a computer which still read the disks, then moving the disks to files that today's computers understand. Once this is complete the files can be read and played again.

The migration of digital files has far more implications than video games, although McDonough believes that video games have become an essential part of our culture and should be preserved as such. However migration and digital preservation in general is incredibly important with born digital files such as emails. In the article "'Digital Dark Age' May Doom Some Data" the perils of proprietary formats are raised. Let's say that you wrote the charter for a new non-profit corporation in Word Perfect file format in the 1990s. Now it's been some time and you want to re-visit your charter. The problem lies that you don't have the machine to read the file format. This is similar to the Duke Nukem problem, except hat a solution is offered. If users create enough demand to do away with proprietary formats, such as .doc, .docx for our files, then it no longer matters which computer we have the files would be ubiquitous and playable. A great example of this in practice is the .mp3 format, which is a non-propietary format and plays in any modern device such as iPhones, Android devices and Microsoft devices.

Looking at the Polar Bear Expedition from the University of Michigan Libraries we see an early example of digital preservation. The Polar Bear Expedition ran into some learning bumps along the way. I believe the project was too ambitious in its expectations. The project uses link paths, which watch what you and other researchers' patterns of use to suggest materials which may be of interest. This is similar to the way that Amazon.com suggests things to you. The main difference here is usage, Amazon.com has ridiculously more users than that Polar Bear Expedition. More users creates stronger suggestions which makes the process work. Also the Polar Bear Expedition had a comments section. Comments only help users if they are used. The lack of comments on this website has unfortunately made this feature rather irrelevant. The Polar Bear Expedition was an ambitious project in 2006, unfortunately it did not derive the number of users necessary for the project to prosper from all of their rather innovative ideas (for 2006).

In closing digital preservation is a interesting field with many challenges. The field is still in its infancy and I believe will continue to grow. In 2009 the New York Times wrote this article highlighting the field and their ideas for growth in the future. The Digital Preservation Europe website said it well when they explained the fragility of digital works:

The same article defined Digital Preservation the best that I found, they said that "Digital Preservation is a set of activities required to make sure digital objects can be located, rendered used, and understood in the future."

|

| A screen shot of Duke Nukem from the Duke Nukem Wikipedia article. |

Looking at the Polar Bear Expedition from the University of Michigan Libraries we see an early example of digital preservation. The Polar Bear Expedition ran into some learning bumps along the way. I believe the project was too ambitious in its expectations. The project uses link paths, which watch what you and other researchers' patterns of use to suggest materials which may be of interest. This is similar to the way that Amazon.com suggests things to you. The main difference here is usage, Amazon.com has ridiculously more users than that Polar Bear Expedition. More users creates stronger suggestions which makes the process work. Also the Polar Bear Expedition had a comments section. Comments only help users if they are used. The lack of comments on this website has unfortunately made this feature rather irrelevant. The Polar Bear Expedition was an ambitious project in 2006, unfortunately it did not derive the number of users necessary for the project to prosper from all of their rather innovative ideas (for 2006).

In closing digital preservation is a interesting field with many challenges. The field is still in its infancy and I believe will continue to grow. In 2009 the New York Times wrote this article highlighting the field and their ideas for growth in the future. The Digital Preservation Europe website said it well when they explained the fragility of digital works:

"Digital objects are fragile because they require various layers of technological mediation before they can be heard, seen or understood by people. Digital objects are also much more venerable to physical damage. One scratch on CD-ROM containing 100 e-books can make the content inaccessible, whereas to damage 100 hard copy books by one scratching move is - fortunately - impossible."

The same article defined Digital Preservation the best that I found, they said that "Digital Preservation is a set of activities required to make sure digital objects can be located, rendered used, and understood in the future."

Monday, November 19, 2012

Campbell House Revised

Amasa B. Campbell was sent by wealthy Ohio speculators to investigate mining opportunities in the west in 1878. In 1892 Mr. Campbell made the front page of the Lawrence Daily Journal when he was caught in the midst of a mining dispute between unioned and non-union miners. Mr. Campbell and his business partner John Finch were ultimately very successful in founding the Standard and Mammoth mines in the vicinity of Wallace, Idaho. These mines became so successful that by 1903, they sold the mines for $3,000,000 to a joint venture backed by the Rockefeller and the Gould families.

The Campbell House was built in 1898 and constructed for $30,000. The Campbell House was home for Mr. Amasa B. Campbell, his wife Grace and their daughter, Helen. Renowned architect Kirtland K Cutter designed every aspect of this house, including the renowned gold reception room, which Cutter borrowed from the rococo French style. Life in the Cutter home was very rigid, with social cues and interactions being paramount. To be invited to dinner at the Campbells was no small feat, the elite would dine formally, their meals prepared and served by servants, the men and women dressed in evening gowns and black ties accordingly. No house of this stature would be complete without a game room. The game room simply belonged to the men, who used the room to play cards and billiards, the game room was the 19th century equivalent of a modern man cave. The house been restored from 1984-2001 by the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, who aimed to restore it as best they could. Unfortunately the original furniture was sold and the MAC has done its best to use photographs and accounts of the home to re-create the furnishings. In 1924 W.W. Powell (formerly Helen Campbell) donated the house to the Eastern Washington Historical Society, who is now known as the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. Guided tours of the house are available and are included in your entrance fee to the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, inquire at the admissions desk.

The Campbell House was built in 1898 and constructed for $30,000. The Campbell House was home for Mr. Amasa B. Campbell, his wife Grace and their daughter, Helen. Renowned architect Kirtland K Cutter designed every aspect of this house, including the renowned gold reception room, which Cutter borrowed from the rococo French style. Life in the Cutter home was very rigid, with social cues and interactions being paramount. To be invited to dinner at the Campbells was no small feat, the elite would dine formally, their meals prepared and served by servants, the men and women dressed in evening gowns and black ties accordingly. No house of this stature would be complete without a game room. The game room simply belonged to the men, who used the room to play cards and billiards, the game room was the 19th century equivalent of a modern man cave. The house been restored from 1984-2001 by the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, who aimed to restore it as best they could. Unfortunately the original furniture was sold and the MAC has done its best to use photographs and accounts of the home to re-create the furnishings. In 1924 W.W. Powell (formerly Helen Campbell) donated the house to the Eastern Washington Historical Society, who is now known as the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. Guided tours of the house are available and are included in your entrance fee to the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, inquire at the admissions desk.

Patsy Clark Mansion Revised

Patrick “Patsy” Clark was an Irish immigrant who came to the United States in 1850. Patsy quickly left New York for the promise of mining opportunities in California. Patsy was wildly successful in his mining overseeing operations and worked in mines from California to Montana and seemingly everywhere in between before working at the Poorman and War Eagle mines in Idaho. Patsy Clark became a well respected mine overseer and was even called upon for his expert opinion when mines were being sold that he was familiar with. In 1889 Patsy proved his business sense by selling the War Eagle mine to a group of investors for nearly 3 quarters of a million dollars in cash. When the new investors inspected their new mine, they found the ore was almost entirely exhausted and would have to begin searching for new reserves within the mine.

Patsy spent much of his life going from Mine to mine, however finally settled down in Spokane in 1889 when he commissioned renowned architect Kirtland Cutter to build him a home. Patsy told Cutter to spare no expense in the construction of his home. Cutter finished the home in 1898, 9 years after Patsy Clark commissioned the home. The Clark Mansion stands as one of the most extravagant homes in the entire Northwest.

Kirtland Cutter spent years trying to create his vision. Inside of the extravagant mansion each major room, such as the Foyer, Drawing Room and Dining Room, had a different architectural style. In total the mansion has 27 rooms if you exclude the attic and basement. Furnishings inside of the mansion were custom built by artisans to Cutter’s specifications. The effect of the mixture of this one of a kind architecture and furnishings produced one of the most stunning homes in what became known as the age of Extravagance in Spokane.

Patsy spent much of his life going from Mine to mine, however finally settled down in Spokane in 1889 when he commissioned renowned architect Kirtland Cutter to build him a home. Patsy told Cutter to spare no expense in the construction of his home. Cutter finished the home in 1898, 9 years after Patsy Clark commissioned the home. The Clark Mansion stands as one of the most extravagant homes in the entire Northwest.

Kirtland Cutter spent years trying to create his vision. Inside of the extravagant mansion each major room, such as the Foyer, Drawing Room and Dining Room, had a different architectural style. In total the mansion has 27 rooms if you exclude the attic and basement. Furnishings inside of the mansion were custom built by artisans to Cutter’s specifications. The effect of the mixture of this one of a kind architecture and furnishings produced one of the most stunning homes in what became known as the age of Extravagance in Spokane.

Friday, November 16, 2012

The MAC

The Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, otherwise known as the MAC has changed a lot over the years. The organization began as the Eastern Washington Historical Society in 1916. The most notable donation to this society was the Campbell House in 1924, which is open and available for tours. In the 1960s the Cheney Cowles museum was opened to exhibit the growing collections the historical society had collected. In 2001 the society opened a new exhibition hall and changed the name to the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture.

Today the MAC is open Wednesday through Saturday to the public as well as tours of the Campbell House. The MAC has three main exhibition halls the museum. Admission to the MAC is $7 for adults, however admission is free during the 'First Friday' events, hosted on the first friday of the month from 5-8PM, and BeGin events on the second friday of every month from 6-8PM.

The MAC also operates The Joel E. Ferris Research Library and Archives to house all of its collections. These archives are accessible Wednesday through Friday 12-5PM, advanced notice is requested.

The Return of the Four-Leggeds

The Return of the Four-Leggeds is an exhibition, permanently on display outside of and in the amphitheater of the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane, Washington. This collection of bronze sculptures was created by New York artist, Tom Otterness and was installed in 2003. Tom Otterness interpreted this work as:

“The Animal people have come with a contract to buy back the world from the Two-Leggeds. The Weasel is negotiating while the Salmon prepare the way to return to the river. The Marmot is already in the amphitheater, munching on small change.”

I believe these statues present a fun an inviting look into social commentary as well as simply being pleasing to the eye. The exhibition is a collection of bronzes regarding this theme, how many bronzes can you find? Take a moment, relax and reflect on The Return of the Four-Leggeds.

“The Animal people have come with a contract to buy back the world from the Two-Leggeds. The Weasel is negotiating while the Salmon prepare the way to return to the river. The Marmot is already in the amphitheater, munching on small change.”

I believe these statues present a fun an inviting look into social commentary as well as simply being pleasing to the eye. The exhibition is a collection of bronzes regarding this theme, how many bronzes can you find? Take a moment, relax and reflect on The Return of the Four-Leggeds.

History of Computing and Data

In The History of Humanities Computing Susan Hockey takes on the monumental task of recounting the entire history of computing as it pertains to the humanities in 14 pages. Perhaps this work should have been re-titled, that is the History of Humanities Computing until 2004. This would have given the reader more of a background of what to expect in terms of content. The beginning of the article entitled Beginnings and Consolidation were great examinations of computing through time. When Susan Hockey discusses the Era of the Internet, the analysis is a little trying. I believe the article should have stopped right before the internet, in order to preserve this as a history of the humanities computing, not the current state of humanities computing.

Looking at the Old Bailey database is a great example of academic search capabilities of websites. The advanced search function enables researchers the ability to search narrowly and broadly. This capability allows academic research along side of casual searchers who want to know how many people were sentenced to death by hanging of chains. The ease of search also helps to browse, you can begin by filtering the database by something you know you want to research, e.g. men, and then peruse the results. The biggest drawback with this browsing style is that you cannot change the amount of results on the page for a given query. What I mean is if there are 50 results you can only view them 10 at a time, rather than seeing all 50 at once. The Old Bailey site has been able to be used by instructors at the college level, such as Ancarett who has been using the Old Bailey database to form the basis of a project for students. This project also allows for the exportation of search data, e.g. how many murders happened between X and Y? The manipulation and export of data allows researchers to use the data in various ways, including visualization projects, which Allen points out can take many different forms.

Allen's article is great in that it reminds us in this technological age that data visualization isn't new. Allen points out visualization project dating back from 1780. What is new is the power and availability of these visualization tools. Allen points out a variety of tools and resources to evaluate not only data but also words. Allen brings up some good points when discussing this and likes to point out that data can be anything, e.g. names, age, sex, location. Allen reminds us that if we take the time to visualize our data it allows us to look at our data differently and perhaps see trends that we hadn't seen before.

One thing to remember when thinking about data and visualization is the key idea, what is data? The first response to a google querry "define:data" is: Facts and statistics collected together for reference or analysis. I liked this definition, however I feel like there is more to it, so I'll leave you with the question: What is data?

Looking at the Old Bailey database is a great example of academic search capabilities of websites. The advanced search function enables researchers the ability to search narrowly and broadly. This capability allows academic research along side of casual searchers who want to know how many people were sentenced to death by hanging of chains. The ease of search also helps to browse, you can begin by filtering the database by something you know you want to research, e.g. men, and then peruse the results. The biggest drawback with this browsing style is that you cannot change the amount of results on the page for a given query. What I mean is if there are 50 results you can only view them 10 at a time, rather than seeing all 50 at once. The Old Bailey site has been able to be used by instructors at the college level, such as Ancarett who has been using the Old Bailey database to form the basis of a project for students. This project also allows for the exportation of search data, e.g. how many murders happened between X and Y? The manipulation and export of data allows researchers to use the data in various ways, including visualization projects, which Allen points out can take many different forms.

Allen's article is great in that it reminds us in this technological age that data visualization isn't new. Allen points out visualization project dating back from 1780. What is new is the power and availability of these visualization tools. Allen points out a variety of tools and resources to evaluate not only data but also words. Allen brings up some good points when discussing this and likes to point out that data can be anything, e.g. names, age, sex, location. Allen reminds us that if we take the time to visualize our data it allows us to look at our data differently and perhaps see trends that we hadn't seen before.

One thing to remember when thinking about data and visualization is the key idea, what is data? The first response to a google querry "define:data" is: Facts and statistics collected together for reference or analysis. I liked this definition, however I feel like there is more to it, so I'll leave you with the question: What is data?

|

| Servers from 2009, courtesy of bandarji on Flickr Commons. Is this data? |

Friday, November 9, 2012

Patsy Clark Mansion

Patrick “Patsy” Clark was an irish immigrant who came to the United States in 1850. Patsy quickly left New York for the promise of mining opportunities in California. Patsy was wildly successful in his mining overseeing operations and worked in mines from California to Montana and seemingly everywhere in between before working at the Poorman and War Eagle mines in Idaho. Patsy Clark became a well respected mine overseer and was even called upon for his expert opinon when mines were being sold that he was familiar with. In 1889 Patsy proved his business sense by selling the War Eagle mine to a group of investors for nearly 3 quarters of a million dollars in cash. When the new investors inspected their new mine, they found the ore was almost entirely exhausted and would have to begin searching for new reserves within the mine.

Campbell House

Amasa B. Campbell was sent by wealthy Ohio speculators to investigate mining opportunities in the west in 1878. In 1892 Mr. Campbell made the front page of the Lawrence Daily Journal when he was caught in the midst of a mining dispute between unioned and non-union miners. Mr. Campbell and his business partner John Finch were ultimately very successful in founding the Standard and Mammoth mines in the vicinity of Wallace, Idaho. These mines became so successful that by 1903, they sold the mines for $3,000,000 to a joint venture backed by the Rockefeller and the Gould families.

Friday, November 2, 2012

Copyright Revisited

I've been reading a lot about copyright lately, more than my non-lawer brain can fathom really, here's what I have found out as copyright pertains to digital history:

On a basic level, copyright is good. Copyright protects the ideas and works of historians. However on a practical level something is wrong with copyright. After reading Helprin in the New York Times I got a striking approval of the copyright. Helprin argues that ideas don't become less important or unique, so why should somebody's work lose its copyright simply because a certain amount of years has expired. Reading Cohen and Rosenzweig their view on copyright is that it is far too confusing, especially for the digital historian. Cohen and Rosenzweig's chapter Owning the Past? goes into the ins and out of copyright in each type of medium. This examination is enough to make your head spin since each medium (text, audio, video and more) has their own unique copyright protocols and loopholes. However C & R do present a great chart which can be useful as a reference.

The idea of the Creative Commons is raised as perhaps the solution to all of this copyright head (and heart) ache. The Creative Commons suggests that people should be allowed to use your work so long as they do not use the work commercially. Creative Commons believes that copyright is owning all of the rights to reproduction of your work while a CC (Creative Commons) Liscense is owning some of the rights to your work. This seems pretty nirvana and groovy until you read Toth's article regarding these liscences. Toth argues about the validity of CC and points out that in principle it seems like a great ideallistic thing to do, but in reality the CC is unenforceable. Toth believes that essentially once you publish something under CC, an action which is irreversable by the code of the CC, you cannot enforce your copyright. Toth believes that once an item is widely available for free it becomes part of the de facto public domain which allows open use by all.

One last viewpoint on Copyright was on Orphan Records. The article set forth by Seidenberg explains the perils of trying to retroactively go back through to find copyright owners for works that were published over 50 years ago. Seidenberg is describing a treasure trove of audio recordings found by a museum. The museum is now trying to find the copyright owner for the records. This process has locked these 'orphan records' in ligigious battles denying the public many forms of access to these records. Seidenberg explains the varrious roles of the legal partners in this battle, essentially scaring digital historians from posting known copyrighted works.

From reading all of these articles I was essentially scared into believing in the value of the copyright. My fresh perspective and intuition tells me to believe everything is copyrighted unless specifically expressed otherwise. Unfortunately for digital historians this attitude produces a lot of barriers, however until things change (and hopefully they do) I'll just have to deal with it.

On a basic level, copyright is good. Copyright protects the ideas and works of historians. However on a practical level something is wrong with copyright. After reading Helprin in the New York Times I got a striking approval of the copyright. Helprin argues that ideas don't become less important or unique, so why should somebody's work lose its copyright simply because a certain amount of years has expired. Reading Cohen and Rosenzweig their view on copyright is that it is far too confusing, especially for the digital historian. Cohen and Rosenzweig's chapter Owning the Past? goes into the ins and out of copyright in each type of medium. This examination is enough to make your head spin since each medium (text, audio, video and more) has their own unique copyright protocols and loopholes. However C & R do present a great chart which can be useful as a reference.

The idea of the Creative Commons is raised as perhaps the solution to all of this copyright head (and heart) ache. The Creative Commons suggests that people should be allowed to use your work so long as they do not use the work commercially. Creative Commons believes that copyright is owning all of the rights to reproduction of your work while a CC (Creative Commons) Liscense is owning some of the rights to your work. This seems pretty nirvana and groovy until you read Toth's article regarding these liscences. Toth argues about the validity of CC and points out that in principle it seems like a great ideallistic thing to do, but in reality the CC is unenforceable. Toth believes that essentially once you publish something under CC, an action which is irreversable by the code of the CC, you cannot enforce your copyright. Toth believes that once an item is widely available for free it becomes part of the de facto public domain which allows open use by all.

One last viewpoint on Copyright was on Orphan Records. The article set forth by Seidenberg explains the perils of trying to retroactively go back through to find copyright owners for works that were published over 50 years ago. Seidenberg is describing a treasure trove of audio recordings found by a museum. The museum is now trying to find the copyright owner for the records. This process has locked these 'orphan records' in ligigious battles denying the public many forms of access to these records. Seidenberg explains the varrious roles of the legal partners in this battle, essentially scaring digital historians from posting known copyrighted works.

From reading all of these articles I was essentially scared into believing in the value of the copyright. My fresh perspective and intuition tells me to believe everything is copyrighted unless specifically expressed otherwise. Unfortunately for digital historians this attitude produces a lot of barriers, however until things change (and hopefully they do) I'll just have to deal with it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)